By Kari Olson Finnegan, BSN, and Liz Ferron, MSW, LICSW

If you have at least one parent age 65 or older and are raising children or financially supporting a child age 18 or older, you’re part of the Sandwich Generation. Coined in 1981 by social worker Dorothy Miller, the term originally referred to women, generally in their 30s and 40s, who were “sandwiched” between young kids, spouses, employers, and aging parents. While the underlying concept remains the same, over time the definition has expanded to include men and to encompass a larger age range, reflecting the trends of delayed childbearing, grown children moving back home, and elderly parents living longer. The societal phenomenon of the Sandwich Generation increasingly is linked to higher levels of stress and financial uncertainty, as well as such downstream effects as depression and greater health impacts in caregivers.

If you’re a clinician and make your living as a caregiver, the Sandwich Generation may feel like a club you don’t really want to belong to. Perhaps you’ve fantasized about quitting your job, leaving your family behind, and decamping to an exotic South Seas island. Of course, you know you’re unlikely to do that. But you also need to avoid the opposite extreme: trying to avoid thinking about your multiple caregiving roles and just soldiering on, typical of many clincians. The impact of caregiving is real and tangible. It must be taken seriously and approached in a way that protects the caregiver’s physical, mental, and financial well-being.

Physical and mental health effects

In a 2007 “Stress in America” report, the American Psychological Association found that Sandwich Generation mothers ages 35 to 54 felt more stress than any other group as they tried to balance giving care to both growing children and aging parents. Nearly 40% reported extreme levels of stress (compared to 29% of 18- to 34-year-olds and 25% of those older than 55). Women reported higher levels of extreme stress than men and felt they were managing their stress less effectively. This affected their personal relationships; 83% reported that relationships with their spouse, children, and other family members were the leading source of stress. Stress also took a toll on their own well-being as they struggled to take better care of themselves.

Another study focusing exclusively on health-related issues found employed family caregivers had significantly higher rates of diabetes, high cholesterol, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cardiovascular disease across all ages and both genders. Depression was one-third more prevalent in family caregivers than non-caregivers, and stress in general and at home was higher across all age and gender cohorts. (See A perfect storm for the Sandwich Generation.)

Reaching out for help

No doubt, some of you reading this article are living the Sandwich Generation experience. As a clinician, you may find it hard to reach out for help and support. But that’s the most important first step—acknowledging that not only is it okay to ask for help, but it’s critically important. Asking for help may reduce the stress associated with fulfilling your responsibilities at home and at work. Clinicians talk a lot about the importance of a work-life balance; such a balance is essential to coping effectively with the many demands faced by clinicians, especially those of the Sandwich Generation.

What does it really mean to balance work and life? In our practice, we see clinicians come to us for help when they feel overwhelmed; many have multiple presenting issues. As we work with them, we learn these issues sometimes are linked. For instance, financial stress can lead to family or relationship strains. Stress, anxiety, and depression can result from juggling too many home and work demands. Being responsible for dependent children or supporting an out-of-work spouse or partner can be daunting. The additional support that grown children and aging parents require can push even the most resilient clinicians past their tipping point.

For some of you, employers may have resources and programs that can help. Providing more flexible scheduling can help employees better handle family responsibilities. Speak to your supervisor to see if together you can devise a plan that allows you to take time off for such things as school events or doctor’s appointments while still meeting your organization’s staffing needs. Some employers offer eldercare benefits, which can help with planning and identifying resources.

It’s also helpful to learn from others. Speak to your human resources department about forming and promoting a lunchtime or after-work support group for “sandwiched” employees to share experiences and resources—and providing the space where the group can meet. Most larger healthcare organizations offer an employee assistance program (EAP), which can provide valuable counseling and support for:

• coping skills and resilience-building

• prioritizing and time management

• setting and maintaining appropriate boundaries

• finding resources to assist with caregiving

• eldercare-related education and resources on financial and life planning for parents

• financial and budget planning to manage your money wisely while planning for your retirement, your children’s college expenses, and other needs.

Some EAPS provide RN peer coaches and master’s-prepared counselors to help employees deal with stressors both inside and outside of work.

Self-care

The following guidelines can help Sandwich Generation clinicians (or anyone, really) take care of themselves.

• Watch for depression. Studies show family caregivers are at higher risk for depression, which may creep up on you. If you or your spouse or partner has access to an EAP, ask those counselors for help with this. Otherwise, if you’re experiencing signs or symptoms of depression, speak to your primary care physician for a more complete screening and assistance or a referral to a therapist or psychologist.

• Put yourself in the “balance” equation. Be intentional about setting aside time for yourself. If you wait until you have free time, you may well be waiting until retirement, leaving you susceptible to burnout. Set aside regular time for self-care, such as by taking a yoga or exercise class or scheduling time to jog with a friend.

• Set boundaries. This ensures you have time to take care of yourself as well as other important things. Be honest about what’s absolutely necessary—and where there’s room for compromise or saying no. Being at your child’s school play? Not negotiable. Baking cookies for the party afterward? No one is likely to remember 15 minutes after the party ends.

• Ask for help. People ask you for help all the time; ask them to return the favor. They can always say no, but most won’t—and may be delighted to lend

a hand.

• Hold family meetings. This is important—to set expectations and boundaries, get help, and enlist others to share some of the responsibilities. Even young children and frail elders can be part of the solution, but you have to let them understand the needs and give them a chance to meet them.

• Find and use a financial planner. You can relieve a lot of stress not only by helping yourself and your parents protect your future and manage the present but also by setting reasonable boundaries and conditions around financial support for grown children

and elders.

For tips on caring for yourself and to learn how to switch on and off to transition from home to work, download and use the Helper Pocket Card.

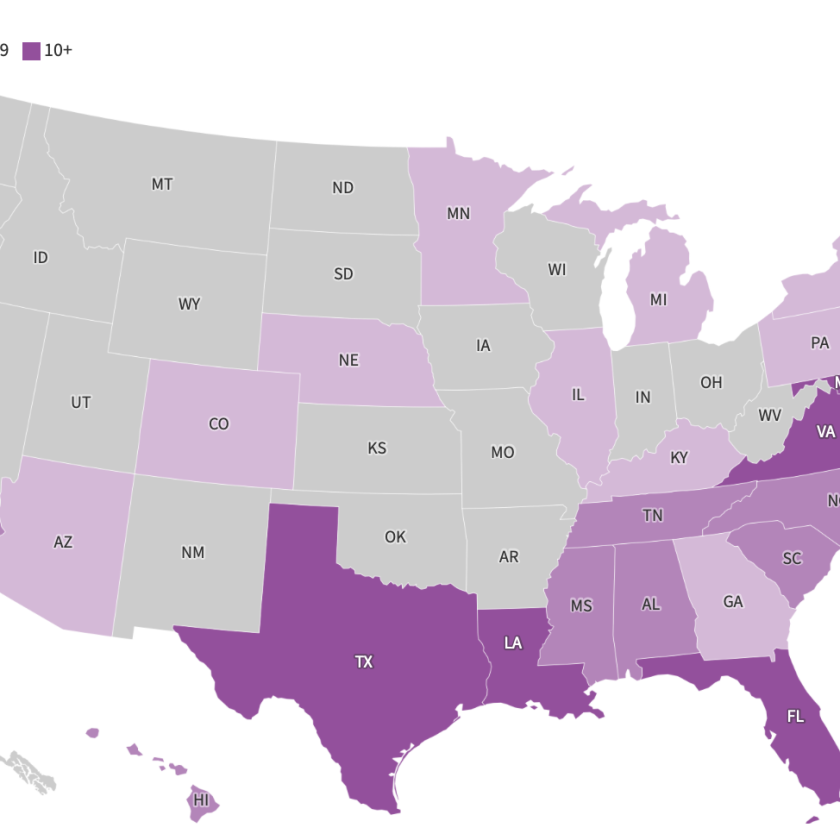

Eldercare can be especially challenging—but many sources of help are available. A good place to start is with the Eldercare Locator, a federally funded service that connects caregivers with local resources (available online at www.eldercare.gov/Eldercare.NET/Public/Index.aspx or by phone: 1-800-677-1116). Every county or multicounty area in the United States has an Area Agency on Aging that receives federal funding to provide information and referral to family caregivers on aging and caregiving services, such as adult day care, respite care, home repair and modification, personal care, and more.

Selected references

Coughlin J. Estimating the impact of caregiving and employment on well-being. Outcomes Insights Health Manag. 2010;2(1):40185. www.pascenter

.org/publications/item.php?id=1092. Accessed May 18, 2014.

MetLife Mature Market Institute. The MetLife study of working caregivers and employer health care costs: new insights and innovations for reducing health care costs for employers. June 2011. www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/

06/mmi-caregiving-costs-working-caregivers.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2014.

MetLife Mature Market Institute, National Alliance for Caregiving, and University of Pittsburgh Institute on Aging. The MetLife study of working caregivers and employer health care costs: double jeopardy for baby boomers caring for their parents. February 2010. www.metlife.com/assets/cao/mmi/publications/

studies/2011/mmi-caregiving-costs-working-caregivers.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2014.

Parker K, Patten E. The sandwich generation: rising financial burdens for middle-aged Americans. Pew Research Center. January 30, 2013. www.pewsocial

trends.org/files/2013/01/Sandwich_Generation_

Report_FINAL_1-29.pdf. Accessed May 24, 2014.

Sandwich generation moms feeling the squeeze. APA Psychology Help Center. May 2008. www.apa.org/helpcenter/sandwich-generation.aspx. Accessed May 18, 2014.

Kari Olson Finnegan is the director of Employee Occupational Health & Safety at Park Nicollet in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Liz Ferron is vice president of Clinical Services at Midwest EAP Solutions, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

DISCLAIMER: All clinical recommendations are intended to assist with determining the appropriate wound therapy for the patient. Responsibility for final decisions and actions related to care of specific patients shall remain the obligation of the institution, its staff, and the patients’ attending physicians. Nothing in this information shall be deemed to constitute the providing of medical care or the diagnosis of any medical condition. Individuals should contact their healthcare providers for medical-related information.